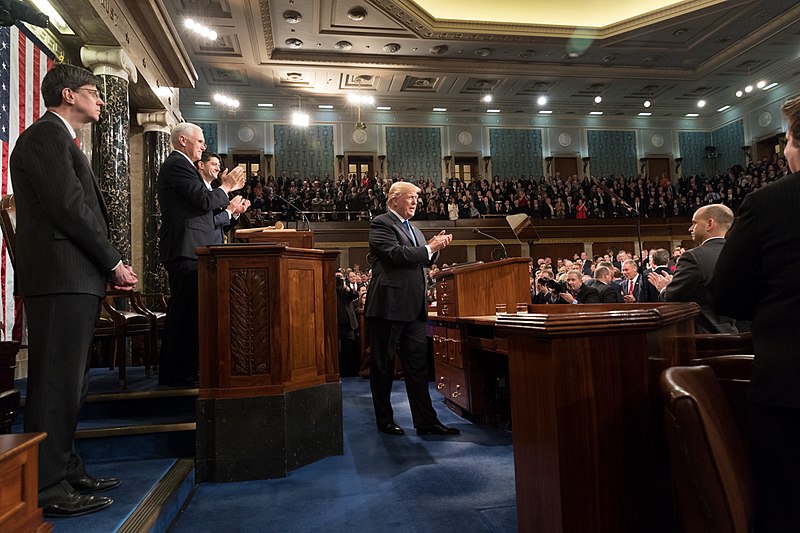

I made the same appeal on Facebook after Trump won in 2016, and most people took it as an anti-Trump political post, which wasn’t how I intended it. So maybe now that the Democrats have won the presidency, I can make my case with credible impartiality. Here’s the pitch:

Whether Republican or Democrat, the President of the United States should not exist.

I may be an oddball for suggesting abolishing the presidency, but I’m in good company. Pulitzer-winning historian Barbara W. Tuchman suggested the same in a controversial 1973 New York Times article. A sizeable contingent of our nation’s founders weren’t too hot on the idea of a president, either—at least not a president with any power. They wanted to get far away from the monarchy they’d fought a revolution to escape, and were worried the president would become a king.

Eventually, they compromised with the Federalists. The executive branch was charged with implementing laws created by congress and interpreted by the courts, but it could not create laws or interpret them itself. The president was never meant to unilaterally rule over the country.

Since the creation of the executive branch, though, the powers of the president have increased considerably, especially in recent decades. We citizens, and our growing political polarization, are partially to blame for this. When our own party’s president in office, we’re content to let them bully the other side, cast aside institutional norms, and test the limits of checks and balances because we agree with the things they’re using their power to do. They’re fighting the good fight! Who cares if they seize a little more power for the executive branch in the process?

In allowing this to happen, we forget that the person who occupies the president’s office has a term limit. Soon, someone from the other party will sit in that office and wield all the extra power we gave the last president. And then it’ll be the other party’s turn to make the same mistake ours just did.

Given this upward spiral of power consolidating around the executive branch, we should stop and ask ourselves: where will this path lead? This question is especially alarming given Congress’s increasing difficulty using its oversight powers to hold the presidency in check. If the president is from their party, congresspersons are too afraid to side against the president. If the president is from the opposing party, they’re too afraid to side with the president. They worry—and rightly so—that their constituents will punish them at the ballot box. Not for their votes, positions, character, or history; for nothing but their positive or negative relationship with the president. We voters so readily buy into the president’s cult of personality and the media narratives that perpetuate it that we’ve tied Congress’s hands.

We can’t rely on most other federal institutions to oversee the president, either. Most federal agencies that could restrain the president if necessary—the FBI, for instance—fall under the president’s control. Tuchman wrote in her New York Times essay: “… The President is subject to no advisers who hold office independently of him. Cabinet ministers and agency chiefs and national security advisers can be and are—as we have lately seen—hired and fired at whim, which means that they are without constitutional power. The result is that too much power and therefore too much risk has become subject to the idiosyncrasies of a single individual at the top, whoever he may be.”

It’s simply not safe for the executive branch to operate at the mercy of a single person’s command. Our government’s checks and balances are clearly strained, but Democrats claim that since Trump is out now, we have proof that the checks and balances work.

They’re forgetting something: Trump isn’t the brightest crayon in the box. Imagine if someone much smarter than Trump, with the same authoritarian predilections, became president. A Republican or a Democrat. Our institutions barely kept Trump in check. Could they really hold this hypothetical intelligent autocrat at bay? Even if this person were someone we mostly admire or agree with, would we really be comfortable handing that person more power, then more power, then even more power just because it’s someone we like?

Far more than I care about who currently has power in the United States, I care that the democratic safeguards my country was founded on continue to be a thing. It’s becoming clearer each year that the stresses being placed on our eighteenth-century system of governance by modern technology, modern economics, and modern ethics just might be too much for it to handle in the long run. We need to make structural, foundational changes to it from a Rawlsian perspective, benefitting every citizen.

We could start by changing the way the president is elected, since we measurably, demonstrably use the worst voting system of any democracy in the world. It’s a very intuitive and easy-to-understand voting system, but beneath the hood, it causes each president to be elected after being preferentially voted for by only about 5% of the population. We can’t really blame our founders for this problem. They were creating one of the first democracies ever, so they didn’t have the advantage of centuries of academic research into voting. They just didn’t know any better way of structuring a voting system so that it more accurately reflects the people’s will.

We do have that advantage, and we have many good options to choose from. Fortunately, there are encouraging examples of states experimenting with different voting systems, and movements to fix U.S. voting that are gaining traction. There’s a lot of work to do.

I think the simplest fix for the problems with the executive branch, though, will be to turn the president into a directory. A directory is a way of organizing an executive branch so that instead of a single head of state, you have multiple heads of state that share power. Together they form a federal council that operates collectively as “the president.”

A common objection to turning presidents into directories is that nothing would ever get done under a directory. But an excellent real-world example flies in this objection’s face. Switzerland has been governed by a directory since 1848, not only at the level of the president, but at every level of its government. And although the system is slightly—emphasis on slightly—slower than having a president, for the most part it works brilliantly.

If this idea seems too extreme, we could even establish that all of the directory’s members will come from whichever party wins the election. I’m not asking for winning parties to share executive power with losing parties; I’m just asking to take power out of the hands of one super-powerful, increasingly king-like “president.” This power should instead be shared among a small group—maybe even as small as three people. To me, this seems like a minimum safeguard against the abuse of power that any rational society should have.

Our federal government is so powerful and resistant to change that this idea won’t get much traction unless demanded en masse by us citizens. That’s unlikely to happen, though, because we like the idea of a president. Something in our psychology deeply wants a single, charismatic leader who our side can rally behind, who will save us from the bad side and show them who’s boss, whose decisions are always just and right and beyond question, and whose fabulousness we can celebrate. This perspective sounds childish, but it’s exactly how many Democrats thought of Obama, and it’s exactly how many Republicans thought of Trump. As devastating as monarchy was (and is) for the world, the human brain seems to be enamored with kings and queens, royal families, Kennedys and Obamas and Bushes who will hand rulership down to their children, and then their children’s children, for us common folk to laud in aeternum.

I say no. The president is our employee, not our friend. Even if we like them, we should never worship them. We should hold them accountable no matter what party they belong to. Even better, we should get rid of the president altogether.

Tuchman finished her plea for a directorial executive branch in the United States with concern that even a directory wouldn’t stop cults of personality from forming in the media. “[A] Cabinet government could not satisfy the American craving for a father‐image or hero or superstar. The only solution I can see to that problem would be to install a dynastic family in the White House for ceremonial purposes, or focus the craving entirely upon the entertainment world, or else to grow up.”