Life for the earliest humans was very different than life is for us. They were at the constant mercy of their environment—if it decided not to give them food, they didn’t eat. They had only minimal shelter from the elements. Many died young. Anywhere they wanted to travel, they had to travel on foot.

Life wasn’t always terrible for them. They enjoyed a high degree of equality—there were no rich or poor, and in many areas women were as powerful and influential as men. There’s evidence that their societies were fairly peaceful, with plenty of leisure time for everyone.

But the fact remains that they depended on their families and tribes for survival in a very harsh world. This cooperation was a key adaptation that helped many mammal species thrive. It’s extremely pronounced in humans. We are social animals.

In a harsh world with limited resources, social animals needed to be certain that their children would survive, so they invested most of their time and resources in their children and formed the most basic social unit: the family. We knew we could trust our families, and we shared everything with them. Their struggles were our struggles. When a family member felt pain or joy, so did we.

This family group, according to philosopher Peter Singer, was the first “circle of ethics:” a hypothetical group with you at its center. You then have altruistic feelings toward everyone else in the circle, and a desire to care for them as much as, if not more than, you care about yourself. We see everyone in our circle as a full-fledged person, with thoughts, goals, fears, and passions not too different from our own.

But in most early societies, the circle of empathy stopped at the family, or not much farther than it. Friends, neighbors, and other tribe members were sometimes important to survival, so when necessary, the circle of empathy expanded to include them. But when resources were scarce and two separate tribes needed a specific resource in order to survive, they fought to the death, because they saw each other as inhuman rivals. This was true especially after the dawn of agriculture, which threw humanity into more frequent violent conflicts.

Agriculture caused more resources to be clumped into one place, which soon made cities necessary. Then the circle of empathy widened to include one’s fellow citizens within a city. Anyone outside the city was, at best, a stranger who didn’t deserve empathy, much less the resources we owned. At worst, they were inhuman, and deserved to die so that we could take their resources.

The histories of the earliest civilizations read as shocking displays of extreme tribalism, with love and affection toward those among the same community, coupled with violent hostility toward those outside the group. As Singer points out, “It is very common for tribal societies to combine a high degree of altruism within the tribe with overt hostility to members of neighboring tribes… Hostility to outsiders is, in fact, a very common phenomenon in social animals.”

Then, even as the first city-states and nations were forming, the Greek philosopher Hierocles realized what was happening. The circle of empathy—a concept Hierocles invented—was expanding wider and wider, and moral progress depended upon the continued expansion of this circle.

But for over two millennia after Hierocles made his observation, the circle of empathy stagnated at the level of the nation. Most people felt fierce loyalty to those within their country’s borders, yet often felt either indifference or hatred toward everyone else. Christians and Muslims fought in destructive crusades. Both religions split into sects whose members didn’t hesitate to openly murder each other.

A few things got the empathy ball rolling again over the course of the second millennium. Beijing, Constantinople, and Venice sprang up as international centers of trade. Merchants realized they could profit by doing business with people outside of their circle, pulling the circle with them as they traveled.

Perhaps the greatest driver of empathy has been the increasing level of literacy over the past few hundred years. Literacy allowed common people, for the first time, to read printed words and view the world from the perspective of those who were different from them. Aristocrats could read novels about the struggles of the lower classes and empathize with them. Indifferent commoners could read about the experiences of slaves, and be compelled to help end the dehumanizing injustice.

As technology increased and travel became cheaper, globalization started changing the empathy landscape, too. Now, regular people could visit other places affordably, meet the people there, and see that those people were very much like themselves. Corporations, once largely confined to their own nations, began to span the globe, enabling huge transfers of ideas and cultures. Continuing this tradition, the internet, despite its flaws, has made us even more familiar with the full variety of human experiences.

The circle of empathy is difficult to measure throughout history, so the story of the circle is admittedly just a story philosophers tell. It waxes and wanes, with frequent backsliding into a small version of the circle. Evidence seems to support its existence, though. Within just the lifetimes of many of today’s elderly, the Western world has seen a dramatic shift in its levels of empathy for persons who are different from the norm.

In fact, I’m going to focus the rest of this blog post on the dominant culture’s circle of empathy in Western world, and the United States in particular, both because its history is the one I’m most familiar with and because this is such a massive topic that wouldn’t be served well by a general, global approach from this point on. I want to get into some detail.

The story I’m about to tell is a rosy, optimistic one. I certainly don’t mean to diminish the hard work, severe suffering, and obstacles we still have to overcome. Progress hasn’t been perfect, and humanity still has many shortcomings.

But on average, the circle of empathy is expanding. In some places it’s smaller than it used to be, and in some places it contracts before it grows again, but it’s steadily growing worldwide. As Dr. King said, the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. And it isn’t just a single circle. Each individual has her own circle of empathy, which grows at whatever pace that individual chooses. It’s worth taking a moment to celebrate our moral progress so far.

My intention is merely to give examples of moral progress rather than provide a comprehensive history. A good example of empathy in the United States of the early 20th Century was FDR’s New Deal legislation. Before the circle of empathy reached the elderly, many had been abandoned as they reached the difficult final decades of life, but this legislation ensured that older U.S. citizens would have a new measure of economic security. It was disastrously flawed because it focused on bolstering the financial security of White people and not Black people, but it was a first step.

The Social Security Act was passed in 1935, followed by the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which prohibited child labor. Before this, children could literally work themselves to death in factories, but now the circle of empathy had grown to include all of the country’s children—not just one’s own children. We realized that children aren’t merely slaves for adults to bestow their labor to—they’re future adults themselves, and full human beings in their own right. Shockingly, the Fair Labor Standards Act did not apply to agricultural work, and to this day children pick nearly one fourth of all food produced in the United States.

Rights for all groups outside of the dominant empathy circle got a major boost in the wake of World War II, when the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which has influenced innumerable laws in nearly every country on Earth.

Around the same time, Indigenous people living under the control of the world’s great empires began to organize politically with unprecedented strength. In Africa, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere, they demanded self-governance and an end to the forced labor and resource extraction that had characterized the era of colonialism. Demonstrations sometimes gave way to armed conflicts and outright revolution, and many Europeans themselves pushed for their empires to be dismantled. On top of this, World War II had left British, French, and other empires with less will and finances for colonial exploitation. Many of the efforts against them succeeded. The rapid decolonization of the world began, and power returned to local peoples in many (but not all) instances. Progress in this area has backslid in decades since, with colonial powers using means other than imperial control to manipulate developing nations. Empathy for people in developing nations, and the recognition that developed nations have profited off of their pain and hardship for centuries, is an especially important hole in our global empathy circle in urgent need of correcting.

Numerous nationalities of immigrants, but especially the Irish, Poles, Italians, and Germans were seen as outsiders in early twentieth-century America, the Irish largely because they brought Catholicism with them. As outrageous as it may seem to us now, it was hugely controversial when the United States elected a Catholic—John F. Kennedy—to the highest office in the land. The dominant U.S. circle of empathy hadn’t expanded to fully include Catholics yet, or the above-mentioned nationalities of immigrants. But once the dominant culture grew accustomed to their presence and their ideas, and saw that they were just normal people rather than outsiders who’d come to destroy America’s way of life, the dominant circle grew. Empathy spread further.

But it still had a long way to go. Most Americans were actually apathetic when they learned about the Holocaust in Europe. It wasn’t happening in their country, after all, so why should it bother them?

In the years during and after the war, Americans of German and Japanese descent were hated tremendously, in spite of the fact that many of them had fled their home countries for America precisely because they opposed their countries’ actions. 120,000 Japanese, most of them American citizens, were forcibly detained in camps inside the United States for a period of four years.

And yet, the circle of empathy soon widened to include the above groups for most of the Western world, and it continued to expand.

Democracy took the circle of empathy out of the hands of the powerful and into the hands of ordinary people. Ever since major democratic movements started in the late eighteenth century, groups within each culture have been able to speak about their marginalization for the first time, and demand equality with the dominant groups.

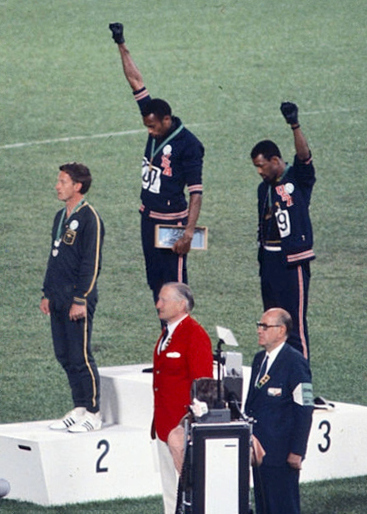

Western women demanded the rights to vote and own property, then reproductive rights, equal employment and pay, and an end to sexual harassment and violence. After the end of slavery in the United States, African Americans demanded education and employment, then voting rights, then an end to racial segregation. These civil rights battles are far from over, and the difficulties facing both African Americans and women are very active. If you’ve only heard about these issues from media sources, I encourage you to click on those Wikipedia links to learn about how we’re in the middle of these civil rights struggles, not at the end of them.

More recently, the Western world has begun to accept gay people into its circle of empathy. Tragically, this didn’t happen soon enough. When HIV was identified as a disease primarily affecting gay men, much of Western culture didn’t care about the problem, including the Reagan Administration, which did little to stop the spread of a disease that would eventually kill almost a million Americans. Attitudes about gay people didn’t begin to change significantly until the early 2000s, but then they changed rapidly. Among the reasons most commonly cited for why straight Americans changed their minds about gay people is that they simply met a gay person, became friends, and realized they weren’t that different.

I think this is one of the most effective ways for the circle of empathy to expand: meeting people who are different from us, seeing and hearing what their lives are like, and celebrating our similarities so that we can learn to celebrate our differences.

The growing circle has its opponents. Many people are very comfortable with how far the circle has grown, or where it is now, and are afraid of its further expansion. Some people’s power or privilege depends on the circle staying where it’s at, and not growing any bigger. There are even those who, despite millennia of evidence against them, continue to insist that everyone outside of the circle are our enemies. The circle of empathy, they say, is already more than wide enough.

This is a very easy thing to say when you are already standing inside of the circle.

The edges of the circle, at least in the West, are just now reaching several types of people they’ve never reached before. Transgender people have been demanding equal treatment for decades, and we’re finally hearing their voices in a big way. Our culture is also starting to include nonbinary people, who aren’t quite male or female, bisexual people, who are somewhere in between gay and straight, and pansexual people, who can be attracted to anyone. We’re realizing that people of all sexual orientations and gender identities are as capable, intelligent, and as deserving of love and affirmation as everyone else.

We’re learning that the current animosity toward Mexican and Syrian immigrants echoes the hostility we once felt toward the Italians and the Irish Catholics, and is just as misguided.

We’re accepting that disabled people face unique challenges in our society that can be difficult for an able-bodied person to recognize, and that we need to change some subtle biases we may have against them. This includes people suffering from poor mental health, who have been heavily stigmatized and deserve our acceptance.

Indigenous peoples have largely been resigned to poverty ever since Americans committed atrocities against their ancestors. The decades-long national conversation we’ve been having about racial discrimination has not typically included Native Americans, which is absurd and tragic, given their history.

Bipartisan empathy is growing for people who are addicted to drugs, who’ve traditionally been seen as degenerates who take from society and give nothing back. But now we’re realizing that this view of addicts is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Research indicates that the best cure for addiction is to welcome addicts back into our communities, to give them love, support, and opportunities. Addicts aren’t perpetrators. They’re victims, not only of a sinister criminal world, but also of a naïve national drug policy that refuses to learn from its mistakes.

After all of the above growth in the circle of empathy, at least in the United States and other parts of the Western world, it’s easy to assume the story stops there. Intuitively, our current social justice struggles seem like the pinnacle of empathy, and we seem so much more enlightened than our ancestors because we’re fighting the good fights.

As a futurist, I question this assumption. We humans have a bias that tells us we’ve stopped growing, that the current version of ourselves is the final version, that all progress has led to this point but won’t go much further.

If you listen carefully, though, you can hear voices trying to get our attention from outside our current circle of empathy. They want to be heard, but we’re not listening. If you look carefully, you can find arguments that suggest horrible injustices are being committed right now. And most of us are unaware of them because our circle of empathy hasn’t expanded far enough to include their victims yet. History is full of well-meaning slave owners and Nazis and their like who thought their own ethics to be the pinnacle of human civilization, only to have them radically overturned when the circle of empathy’s expansion revealed their ethics to be horribly defective. We’d be wise to make sure we aren’t under similar delusions about our current ethics.

This next part is just conjecture, of course, but I think and hope that the circle of empathy will expand farther in the future—much farther.

I don’t think the world has really grasped its backbreaking oppression of the poor yet. Poverty is widely seen as an “unsolvable” problem. Most of the sentiments toward helping the poor are either vague hand-waves that people should give more to charity, or callous reprimands to the poor for not being richer, because their situation is seen as being their own fault. Most large-scale political efforts to help the poor are dismissed by many as dangerous Communism. Even among the popular social justice movements, the poor among any given oppressed group are usually given far less of a voice, and their interests are considered far less of a priority than those of their wealthier counterparts. I think humanity’s circle of empathy will eventually realize that the poor were born into their situation, and that even the hardest of workers can’t climb out of poverty without the knowledge of how to do so, and without opportunity to do so. We’ll eventually view poor people and homeless people as people just like the rest of us, but whom circumstances deprived of any path toward financial wellbeing. We, with our globe-spanning vacations, $30,000 weddings, and mountains of Christmas gifts, will see that we’re morally obligated to spend much of our money helping poorer people—especially those in less developed nations. Our money will go where it can ease the most suffering instead of being arbitrarily spent benefitting “us and our own.”

Similarly, I think we’ll realize the moral shortcomings of the concept of citizenship: the idea that the accident of where we were born should determine how far we’re able to go in life and what type of government we live under. We’ll see that our protectionism and defensiveness of national borders is barely less arbitrary than if we were just as defensive of state or city borders. I think that eventually, the circle of empathy will swallow the world’s borders completely, and migrants will be able to come and go as they please. Becoming a citizen of any country will be as easy and painless as filling out a brief form online.

Flying on the shoulders of gay rights, I think we’ll recognize a whole slew of different forms that love and sex can take. Our sex-driven society will begin to recognize and accept asexual people. Our monogamy-obsessed culture will start to see polyamorous relationships as legitimate. And these will be just the beginning. Morality, we’ll learn, has nothing to do with our private parts and how we use them, as long as what we’re doing isn’t harming anyone.

I think we’ll also start to perceive the vast array of subtle yet pervasive biases that can harm people in groups that aren’t traditionally considered disadvantaged, like lookism, bias against introverts, and bias against single people. We’ll move to empathize with the people these biases effect, and end the biases as best we can. Society’s immense prejudice against people with low intelligence, which consigns them to menial, low-paying labor for life, will likewise abate as we start to view them as people who had no choice about their brains’ aptitude, and so do not deserve to be penalized for it.

Empathy will also extend to criminals. Even the worst ones: murderers, rapists, child molesters. This is a tough one, because we humans naturally crave vengeance when someone has wronged us, and even more so for those who have wronged us as much as these types of criminals. But social science has shown us that most criminals—even the hardest, nastiest ones—can be rehabilitated. We can build prisons to mold criminals into good people, who are able to fully reintegrate with society and contribute to it in meaningful ways. This doesn’t change what they did. And for the victims, I understand how tough to swallow this idea can be. But what is better for society as a whole? Is it better if we use our prisons to destroy what little emotional and social health criminals already have, and restrict them from ever making positive changes to their lives? Or is it better if we focus on healing the problems in prisoners’ minds, updating their values to reflect our own, and showing compassion to them so that they might grow into compassionate people one day, too?

Our circle of empathy will also include animals in the future. Not just the cute and cuddly ones, but all animals that are conscious and capable of feeling pain. Science suggests that consciousness is a spectrum, with no sharp line dividing humans from the rest of the animal kingdom—only a gentle gradient. With enough time, chimpanzees, dolphins, or octopuses could easily have risen to humans’ level of intelligence. But we got here first. It’s also clear that most of the animals we like to eat can feel pain, and that many of them perceive the world at at least the level of a dog or a cat. Pigs, in fact, have a much higher level of consciousness than dogs and cats. On intelligence tests, pigs score at about the level of human toddlers… and yet we eat them. How might we feel if pigs had gotten to the threshold of sentience before we did, and they decided to eat us instead?

Further in the future, humanity will stop fetishizing work as the single most important measure of the value of a person’s life, and our circle of empathy will extend to nonworking people. These are people who can work, but choose not to. Today they are shamed, and we think something must be deficient with someone who prefers not to work. Our brains are still wired for the world of ancient days, when resources were scarce and our circle of empathy was small, so we get angry at these people for taking from society while contributing nothing. But whether or not people choose to work, many of us will be forced not to work in the future due to increasing automation of the workforce. Such a great number of us will be nonworkers that we’ll need to develop empathy for nonworkers, and build a society where they can coexist with us.

So far, our circle of empathy has transcended space, culture, and identity, but in the future, our circle will grow so wide that it will even transcend time. When making decisions about our world, we’ll take future people into account. We’ll empathize with our descendants.

If humanity does prosper in the future, then the amount of future people is infinitely greater than the amount of past people, and the burden of protecting them rests on the shoulders of the living—on our shoulders. We are the ones who currently hold stewardship of the planet they will one day inherit. If we truly empathized with these future people, would we even for a second think about building bombs so powerful they could destroy the planet? Would we dare to raze nature as boldly and as quickly as we’re doing now? Would we be so eager to fight with each other, knowing from our history how wars can escalate into devastating loss of human life? Future people, if they do exist after the choices we make in our time, will likely look back on us the way we look back on our own ancestors, wondering how our circle of empathy could ever have been so small. So even if no other reason for expanding the circle of empathy is deemed important, we should at least consider the legacy we’ll leave if we refuse to expand it.

Even today, with humanity’s empathy extending farther than it ever has before, many people prefer to keep their circle of empathy small. Many people are stuck way back at the beginning of the empathy path, prioritizing their family, their tribe, their nation, or other people similar to them at the expense of anyone else they may need to ignore or trample to ensure their own prosperity.

We need to extend our circle of empathy to include these people, too.

When you still live in a small empathy circle where you see resources as limited and everyone outside the circle as a potential enemy, you live in a place of fear. Because of that fear, it may take ages for the people still living in these small empathy circles to join the rest of us in our globe-sized circle. If we want them to do so, it is folly for us to sit comfortably on our side of the empathy chasm, demand they take a blind leap across that chasm, and then jeer at them for their perceived foolishness when they quite understandably refuse to do so. When we do this, it just confirms everything they believe about people outside of their circle being enemies who want to conquer them and their way of life.

Instead, we need to meet them where they’re at. Once you get to know them, you’ll find that people in even the smallest of empathy circles have strong moral centers. They just haven’t expanded them yet.

We, with our wider circles of empathy, are the ones who know how freeing they can be. We shouldn’t expect someone who’s never experienced that to know what it’s like. Such knowledge is itself a form of privilege. So we need to build bridges, forged from the fibers of our own circles of empathy, across that chasm. We need to greet the people on the other side warmly, hold their hands, and walk them slowly over to our side of the chasm, being kind and patient if they stumble along the way, and understanding if they get angry at us or want to go back to their smaller circle for a while.

I see this as the most productive path toward the vision Hierocles first saw in 200 B.C.E.: empathy from the entire human species, for the entire human species, including every individual who comprises it. This is how we collectively realize that every person deserves full human rights, has a mind of their own, can contribute to society, deserves love and affirmation, and can have a prosperous future if they’re allowed to do so. This is how we can best spread the joy and purpose of living a life not just for one’s own prosperity, or one’s family’s, or one’s nation’s, but for the prosperity of one’s entire world.

We’ve come a long way since the time of the early humans. Advancing technology, ethics, and reason have made our world much less harsh. Resources—at least the most essential ones—are plentiful. We have the opportunity to push our circle of empathy to new limits, to continue this grand story of human moral progress, to empathize with more vigor and compassion than we ever have before.

So let’s do it.

Peter Singer’s short-but-pithy book The Expanding Circle uses science and philosophy to explain why the circle is expanding, which is a subject I barely touched on above, because I’m nowhere near as smart as Peter Singer. The above blog post is very much not a synopsis of his book—there’s almost no overlap between them—so I highly recommend the book if you’re interested in the topic.

In addition, two of my favorite filmmakers—the Wachowski sisters—have made the expanding circle of empathy the central idea of their lives’ work. If the concept interests you, I can’t recommend their films highly enough. Start with their masterpiece Cloud Atlas, and if you like it, similar themes lie at the center of their brilliant Netflix show, Sense8. If you like that, you can also find these themes discussed to a lesser extent in the Wachowskis’ earlier, more obscure, barely known work, The Matrix Trilogy.